for the Implementation of International Standards

related to Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)

Disclaimer

This e-learning module has been developed for the teaching purposes and material contained in it is of general nature.

It is not intended to be relied upon as legal advice and the concepts and comments may not be applicable in all circumtances.

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)

This section is dedicated PRA

- Why is it done?

- How is it done?

- What are the challenges?

From our previous units

Phytosanitary measures should be based on international standards where they exit (IPPC’s ISPMs), however national or regional phytosanitary measures can be applied as long as they are technically justified and address the risk appropriately.

How to choose these measures? Through a process called Pest Risk Analysis (PRA) if, and only if, there are no available international phytosanitary measures or standards to address the risk posed by the pest.

Shifting the decision-making process towards scientific justification

-

The SPS Agreement’s purpose is to limit putative claims for protectionist reasons which could lead to potential trade barriers.

-

The SPS Agreement’s purpose is to establish templates for risk management decisions.

Risk assessment and PRAs

This unit focuses on:

Steps and types of PRAs:

- The 3 PRAs steps;

- PRAs and Import Risk Analysis (IRAs);

- Group & regional PRAs.

Examples and resources:

- PRA, IRA, Regional, Group PRAs;

- Qualitative vs Quantitative;

- Databases and tools.

The objective is

To provide you with the necessary information and processes to carry out PRAs

PRA in ISPM 5, is defined as: “Process of evaluating biological or other scientific and economic evidence to determine whether a pest should be regulated and the strength of any phytosanitary measures to be taken against it”. [ISPM2, 1995; revised IPPC, 1997; ISPM2, 2007]

PRA is a science-based decision-making process to select the most appropriate phytosanitary measures for a specific pest or pathway. PRAs can be used to define the status of a pest too. PRAs are core instruments for preventing plant pest introductions.

The focus of a PRA may be a commodity or a category of commodities (e.g. citrus), a specific pest or group of pests (e.g. several Phytophthora species on imported plant material for the nursery industry), or the method of conveyance of the pest or commodity (e.g. import of coco peat as growing medium).

An Import Risk Analysis (an IRA) is a commodity-based PRA. IRAs (or BIRA for Biosecurity Import Risk Analysis in Australia) is therefore a collection of PRAs for a specific commodity.

A pathway is : “any means of entry or spread for pests and diseases”.

Pathways and risk are two related concepts that are very important to understand for PRAs.

To understand how a pest can enter and spread in a new territory, one needs to understand how it can arrive and enter a new territory, its biology and its propensity to establish and spread. Therefore another important concept is the mode of dispersal and entry of a pest.

There are two major modes of dispersal that need to be considered when conducting PRAs.

Natural means: Non-human assisted dispersal (includes entry and spread)

Other: Human-assisted via the transportation of goods, commodities, packaging, conveyances and via travel

Pests can be found in or on plants and plant products, which are referred to as commodities (see the definition tab 6 for the difference between commodities and goods).

The commodity itself can be infected or infested by a range of pests e.g seed-borne virues or the mango seed weevil larvae (Sternochetus mangiferae)

Pests can also be found on rather than in the commodity but still are the result of an infestation or infection starting in the field or occurring later on, during storage and transport e.g scales or mealybugs infestations.

Some of these pests are commodity-specific whilst others are not.

Examples of commodity, or plant and plant product-specific pests are citrus canker on citrus, or mango seed weevil in mangoes.

Examples of pests commonly found across a broad range of commodities are scales, aphids and mites.

Image: Mango seed weevil infestation of fresh mangoes, Department of Agriculture and Food, western Australia

Pests can also be transported passively through packaging and conveyances. They can be found in cardboard boxes, pallets, ropes, containers, in or on ship, vehicles, equipment, planes etc.

These contaminating or hitchhiker pests have the potential to impact on plant health.

An example is the Giant African Snail (GAS), Achatina sp, which is spreading around the world on containers, boxes and pallets.

Other pests can be introduced that way, including a whole range of ant species such as the red imported fire ant (RIFA, or Solenopsis invicta), a whole range of invertebrates feeding on cardboard or wood packaging (Silvanidae, or Mycetophagidae), the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) and the brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys).

There is another category of pests that have never been associated with any plant or plant products in the past and therefore were never recognised as potential pests.

An example is Phytophthora ramorum causing sudden oak death and many recent forestry pests in the UK and the US.

These can end up becoming high-impact species that were never previously recognised as high-threats to productions systems.

A commodity is a raw material used to manufacture a finished good.

A product, on the other hand, is the finished good sold to consumers.

Conveyances are transport means, including shipping containers, ships, planes, air cargo containers.

Both commodities and products are part or the production and manufacturing process-the main difference being where they are in the chain.

PRAs are developed and are used by NPPOs decide whether pests should be regulated or not as quarantine pest (and therefore define pest status as seen in slide 8.1), and propose risk management options to mitigate the risk the pose to their countries.

A PRA is a science-based process that provides the rational for determining appropriate phytosanitary measures using technical, scientific, and economic evidence to determine whether an organism is a potential pest or plants and their products, and how it should be managed.

PRA is a multidisciplinary field that requires some knowledge in botany, entomology, general plant pathology, mycology, virology, bacteriology, ecology, invasion biology, economics, and modelling.

Access to a range of experts and colleagues might be necessary to complete PRAs. PRAs rely on team work and expert advice.

Every PRA will be different to reflect local conditions, production systems, political and economic situations and of course each ALOP.

A PRA is a science-based decision-making process to select the appropriate phytosanitary measures, or group of phytosanitary measures for a given pest or group of pests.

By doing a PRA, one evaluates the evidence to determine whether an organism:

- is a pest;

- need regulation;

- need phytosanitary measures to manage its risk.

There are 3 ISPMs directly relevant to the development of PRAs plus a whole range of additional ISPMs indirectly related.

ISPM No. 2: “Framework for pest risk analysis”. This standard describes the overall process of PRA for pests of plants.

ISPM No. 11: “Pest risk analysis for quarantine pests”. This standard describes the factors to consider when conducting a PRA to determine if a pest is a quarantine pest. The emphasis is in ISPM No. 11 is on the pest risk assessment and risk management components of PRA, although the full PRA process is covered.

ISPM No. 21: “Pest risk analysis for regulated non-quarantine pests”. This standard provides guidelines for conducting PRAs on regulated non-quarantine pests.

There are several other ISPMs that are relevant to the development of PRAs including ISPMs No. 3, 4, 6, 8, 14, 17, 19, 24, 32, and most recent ISPMs 35, 36, 38 to 41.

For a list of current (September 2019) ISPMs, click here.

PRAs are dedicated to 2 categories of pests recognised by the IPPC:

Quarantine Pests (QPs) and Regulated Non-Quarantine Pests (RNQPs).

PRAs can also be initiated for specific commodities or pathways; these are commodity-initiated PRAs or Import Risk Analysis (IRAs).

PRAs can also be initiated for commodities that pose a risk themselves such as plants for planting that can become invasive weeds (ornamental plants from the nursery industry and amenity plantings, pasture species, etc.), beneficial organisms or biological control agents (BCAs).

There is another type of PRAs called Group PRAs that focus on group of pests that are found systematically on a broad range of commodities or a range of import pathways. Example of these group PRAs for thrips, mealybugs, and scales.

A PRA process can be initiated for:

- The identification of high-risk pests or specific commodities, or groups of commodities or pathways (in other words to define pest status);

- The identification of organisms not previously identified as pests of plants (such as weeds, Biological Control Agents (BCAs) or other beneficial organisms or new pests);

- To review pathways and means of entry for pests themselves or imports; and

- To review and amend current policy and processes.

A PRA can be dedicated to plants and plant products (commodities), individually or in a group of commodities.

They can also be developed for individual pathways or group of pathways.

They can focus on specific pests or groups of pests.

They can be developed for conveyances.

Introduction

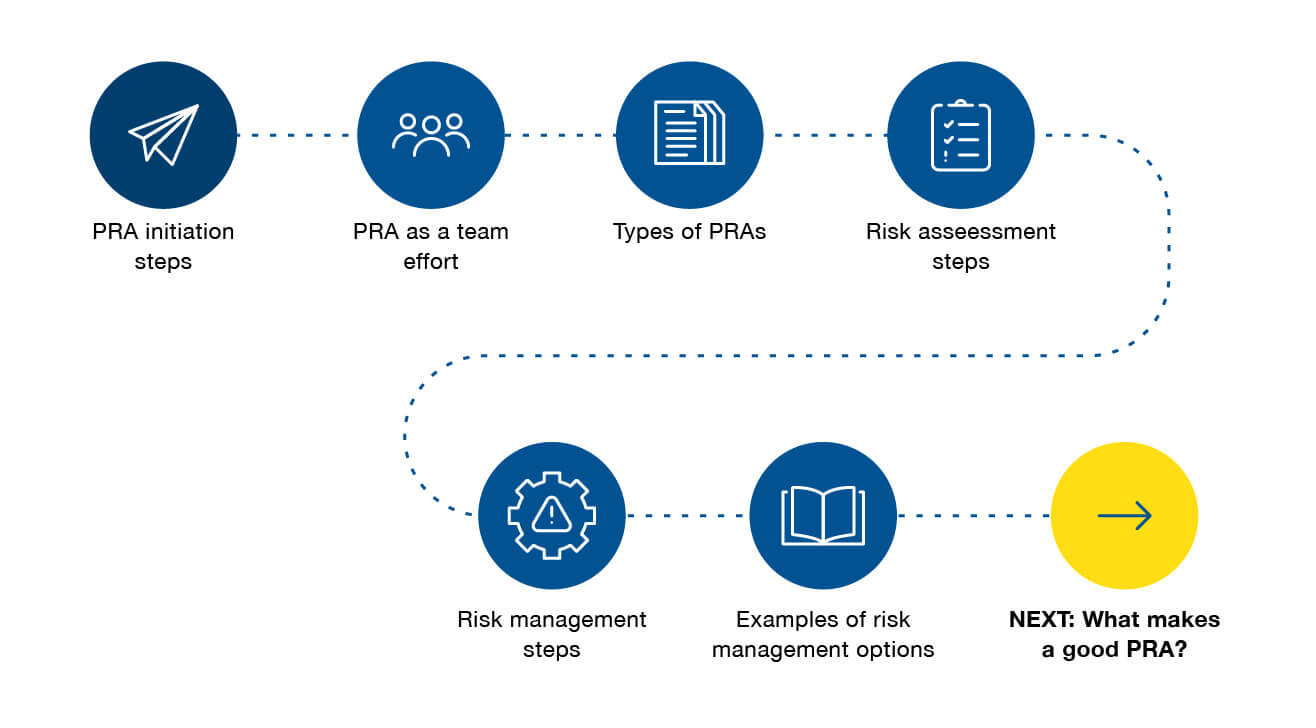

The development of a PRA follows a series of very well-defined steps.

There is already a PRA document developed specifically for ASEAN countries. The IPPC has a whole range of material, included e-learning courses and documents dedicated to PRAs.

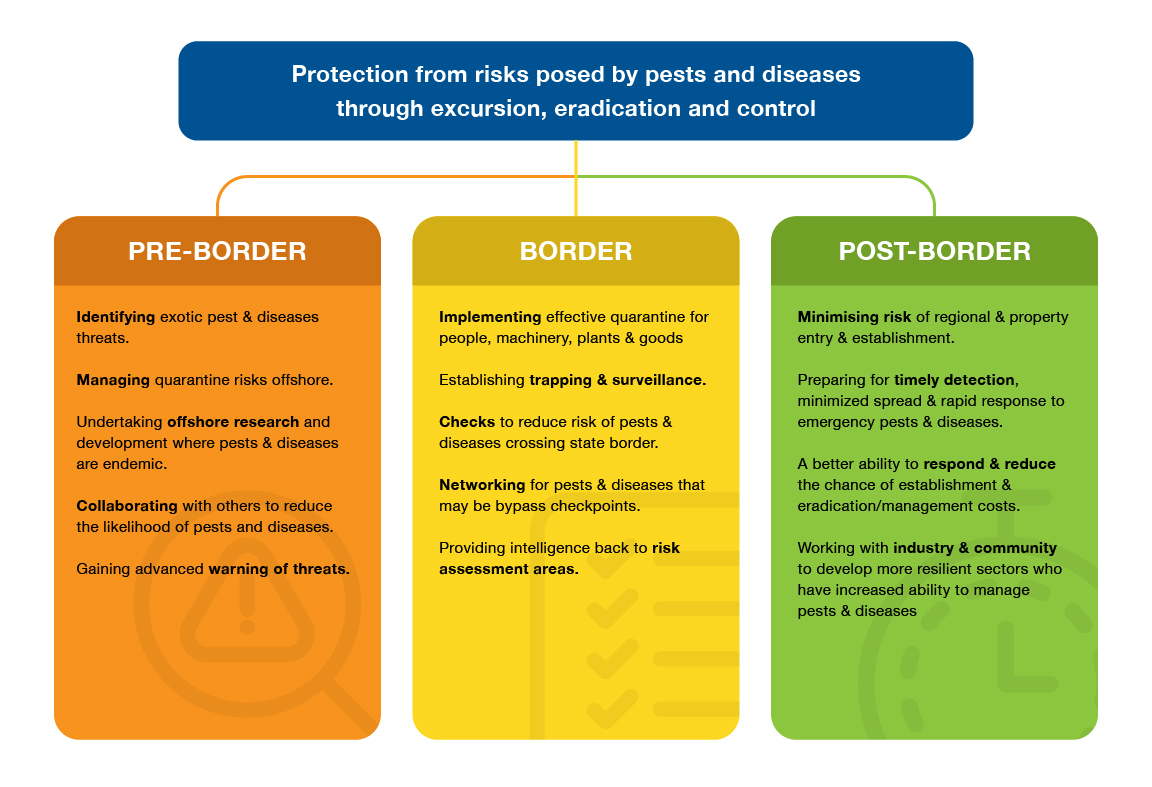

Here is a summary of the PRA stages.

Step 1, the initiation step has already been discussed.

Image Source: GUIDELINES FOR THE CONDUCT OF PEST RISK ANALYSIS FOR ASEAN COUNTRIES

PRA area

PRA area: “The PRA area is the area potentially at risk. It can be a country, a fraction of country, several countries or a region”.

ISPM No. 5 defines the PRA area as: “the area in relation to which the pest risk analysis is conducted”.

Stage 1: Initiation

The first step of a PRA is the initiation stage.

During the initiation stage, the aim is to identify a risk, and associate it with a cause, a pest or a pathway.

The questions to answer here are:

- Is the risk posed by a pest, or a group of pests?

- Or is the risk posed by a commodity or groups of commodities?

- Is the risk linked to a single pathways or groups of pathways?

- Or is it linked to a conveyance or conveyances?

It is about who, what, where and how and gathering the relevant information.

The impact needs to be defined in this first stage.

The other step in the initiation stage, is to check if any PRAs have already been done and are available. They might just need updating.

At the end of the initiation stage, you should know about the reason why you are initiating a PRA and you should have a list of pests either associated to a pathway or pathways, a commodity or commodities, or conveyance or conveyances. You should also have identified the PRA area.

Example of initiation phase (pathway)

Imagine you have a request to import Achacha (Garcinia humilis) from a new country of origin.

You would initiate a PRA.

During the initiation phase, you would:

- Review the available information in the documentation provided by the exporter and the information available from the NPPO from the country of origin;

- Review the published literature on the host: in our case achacha, taxonomy, biology and phenology, how they are grown, harvested, sorted and packed for the export market;

- Check the potential occurrence and pest impact along the whole product chain: gather and review information on all pests associated with the fruit, their taxonomy, biology and life cycles, if they can impact related hosts in the broader environment, and what would be the impact;

- Gather information on the industry, where the fruit are grown, the value of industry, and current market;

- Review previous PRAs on that very species or related species;

- Scan pest records and peer-reviewed publications to generate a list of the pests potentially associated with that plant species in the country of origin.

Once a draft list has been compiled, you would refine it by:

- removing from the list any pests that might not be associated with the achacha fruit (but present on the rest of the plant);

- remove from the list any pests that are not likely to be present at the time of harvest, when the fruit are picked;

- remove pests that might be eliminated during cleaning, sorting and packing of the fruit.

Image source: Achacha fruit, ITQ

Examples of initiation phase (putative PRA on a specific pest)

So a pathway PRA (or in that case an IRA), is a collection of pest PRAs for which the identified pathway is identical.

This is a second case scenario:

Imagine you are already importing fresh bananas from one of your trading partners.

One of the NPPOs in your region just informed you of an emerging pest (for instance, Xanthomonas campestris pv musacearum) on the continent you are importing your bananas from.

You would start a PRA for this pest with the aim of amending your current import conditions to appropriately address this potential new risk.

You would:

- Gather information on this pest from the NPPO of the country of origin, gather additional information on taxonomy, country of origin, host range (does it infect all banana cultivars and several other species in this family?), its life cycle and life stages, the mode of dispersal and viability of inoculum. And you would fully reference it all.

- You would check how this pest can enter and spread in your territories, and prepare a list of pathways of entry and pathways of spread.

- You would also gather information on your own industry, banana growing areas, the susceptibly of the cultivars you are growing, the value of the industry, the cost of the potential treatments to apply (if any) and you would also check if there are any wild relatives in the Musaceae family in your territories, where they are found, and what would the impact of this pest be.

Image source: Blomme et al. (2017)

Stage 2: Risk assessment

The second stage after initiation, is about assessing the risk itself.

You will need to assess the risk associated with either individual or groups of pest(s), commodity(ies), pathway(s) or conveyance(s) and compare it to your ALOP to define whether the risk is acceptable or not.

Pest risk is defined as a probability of introduction by (multiplied by) the impact of introduction.

The magnitude of impact is defined as the sum of the cumulative economic, social and environmental impacts.

Acceptable and unacceptable risks in the SPS Agreement unit were presented in earlier modules when discussing the concept of ALOP.

Note that assessing the risk of emerging pests is very difficult because of the lack of information on the pest biology, epidemiology and its behaviour outside of its country of origin.

Stage 2: Types of risk assessments

There are 3 types of Risk Assessments:

Qualitative: Uses non-numerical terms and relies on judgement of the likelihood of entry, establishment and spread and the severity of its consequences. The outcome of this process is a ranking using for instance the following terms: negligible, low, medium, high, very high.

Quantitative: Uses modeling for the calculation of probabilities and risk. For these sufficient quantitative data needs to be available – which is rarely the case.

Semi-quantitative: A combination of the two methods discussed above. Quantitative methods are used when they are available. For instance you might use a modeling software like Climex to predict the distribution and spread of the pest in specific climate zones.

In this step, the analyst will need to use his or her judgment to assess the risk based on the information provided by experts and peer-reviewed publications.

Image source: fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) (J.E. Smith), Frank Peairis, Colorado State University.

Additional information from the IPPC on the fall army worm can be found on here.

Stage 2: Risk assessments steps

There are 3 steps in Risk Assessment:

Step 1: pest categorisation: PRAs should be initiated for pests that are “not present” or “present, but not widely distributed” in the PRA area and “under official control”, which includes under eradication, containment or management of regulated non-quarantine pests.

Step 2: assessment of the probability of introduction (entry and establishment) and spread of the pest to eventually define an overall risk.

Step 3: assessment of potential impacts of introduction and spread.

Image Source: South American Fruit Fly, Photo by Taina Litwak, USDA ARS. The Bugwood Network.

Stage 2: Pest categorisation

Pest categorisation will allow you to define if the single pest, or group of pests on your list of pests associated with your pathway, satisfies the criteria of quarantine pest or regulated non-quarantine pest.

The questions here are:

- Does the pest meet the criteria for a quarantine pest?

- What is the potential for the pest to be associated with the commodity or pathway?

- What is the potential impact of the pest?

- How likely is introduction and establishment of the pest if no mitigation measures are applied to the pathway(s)?

ISPM 11 will apply if you have determined that the pest is a quarantine pest, ISPM 21 will apply to regulated non-quarantine pests.

Stage 2: Probability of introduction

The next step is to evaluate the probability of introduction. “Introduction” of a pest involves both entry and establishment. So the pest must first arrive in the new territory, survive and start to establish a population.

For pathway initiated PRAs, one needs to assess the probability of introduction for each of the pathways a pest might be associated with, from its origin to its establishment in the PRA area. So it includes:

- The probability of being associated with the pathway at origin,

- The probability of survival during transport,

- The probability of transfer onto a suitable host,

- The probability of establishment,

- Presence and availability of alternate hosts (remember our barberry and rust story?), the presence vectors (for bacteria, viruses, viroids and phytoplasma) and the presence reservoir hosts.

- And the overall suitability of the environment.

In here, you might include any other relevant information relating to reproductive strategies (Presence or absence of compatible mating types for Phytophthora spp. for instance), host resistance, genetic adaptability, minimum population levels or thresholds for establishment (e.g. a gravid European honey bee queen is not enough to establish a colony – she needs workers).

Stage 2: Economic impact (1)

During this step, it is essential to gather evidence on the potential economic impact of the pest.

Remember that this is a very important aspect of a PRA. Under ISPM 5, organisms are pests if they cause some unacceptable direct or indirect economic impacts, where they are introduced.

So it needs to be made very clear that the pest has the potential to have an unacceptable economic impact in the PRA area.

Pests that have no potential impacts in the PRA area (e.g. because no hosts are present, or because climatic conditions are not conducive to establishment), are not quarantine pests and should not be considered further.

Stage 2: Economic impact (2)

During this step, the purpose is to identify and quantify, as much as possible, the potential impacts that would result from a pest introduction and spread.

Some of these direct and indirect impacts may be:

- Economic (direct yield losses for instance, increase in cost of production due to control measures, loss of export markets or loss of access to future export markets);

- Environmental (e.g. the pest might affect endemic tree species in national parks)

- Social impact (e.g. loss of employment on farms, or packing facilities)

- Religious impacts (e.g. red palm weevils – Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Oliv killing date palms in North Africa).

- Change in domestic and foreign consumer demand,

- The possibility of the pest to act as a vector for an endemic species or the possibility to act as a vector for a quarantine pest or a RNQP,

- Impact on recreational activities and tourism and (e.g. The red imported fire ant stopping people from accessing parks and sporting venues).

Image source: Rhynchophorus ferrugineus affecting date palms

Stage 2: Analytical tools

There are many analytical tools available to assess the economic impact in a PRA. The 3 analytical techniques I have listed below would require the assistance of an economist.

Partial budgeting: The aim of the analysis is to estimate the financial impact of the change.

Partial equilibrium analysis: This technique is recommended if a significant change in producer profits or consumer demand is expected.

General equilibrium analysis: This analysis attempts to give an understanding of the whole economy and is appropriate if the economic changes are significant at the national level.

The conclusion of the economical impact can be either:

- Numerical (e.g. the pest is estimated to cause 10 million $ damage to the pineapple industry annually),

- Qualitative (e.g. the pest is expected to cause a very high level of damage),

- Or semi-quantitative, combining both qualitative and quantitative measures.

Stage 2: Overall assessment

The overall assessment of pest risk will require the combination of likelihood of pest introduction and consequences of that introduction, if it occurs. For pathway-initiated PRAs or IRAs, each pest will need to be dealt with individually.

The final pest risk assessment rating can be done many ways:

- numerically (quantitatively),

- qualitatively,

- semi-quantitatively,

All will depend on the time allocated to the PRA or IRA, the resources, the availability of information and data for modelling. Often risk analysts have little time and limited budgets.

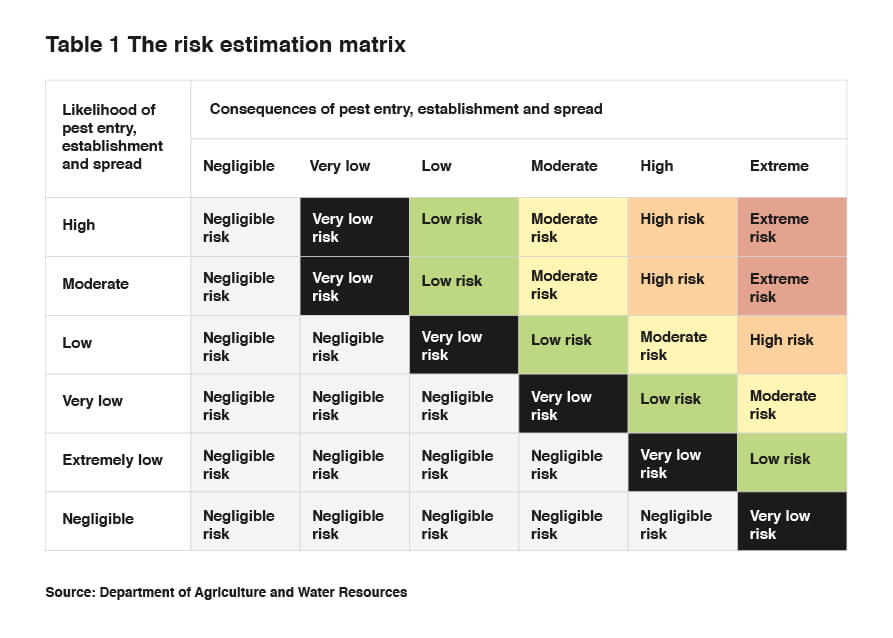

The overall risk rating can be assigned and utilised in the next stage of PRA, pest risk management. Often people tend to use risk matrices. An example is attached.

Image source: Department of Agriculture, Australia

Stage 3: Risk management

This last stage is dedicated to the level of acceptability of the risk and the selection of potential management options to lower the overall risk to an acceptable level to meet the ALOP.

The questions to answer for the risk management phase are:

- What can be done and what are the options?

- What are the trade-offs?

- What are the cost-benefits?

- What are the impacts of the risk management decisions?

This phase aims to determine:

- What is the efficacy of the mitigation strategies,

- Working out if these are feasible and,

- Finding out if other options are available to get to the same result.

Stage 3: Selection of measures

The measures selected should be:

- Feasible and cost-effective;

- The least trade-restrictive possible;

- Equivalent options should be considered if there are any;

- Selected measure should appropriately adress the risk.

Total prohibition is an option if no measure exists that can lower the risk sufficiently.

There might or might not be any “official” phytosanitary measures available to mitigate the risk. National or regional protocols, different from the current ISPMs, can be implemented if they address the risk appropriately.

Stage 3: Example of risk management options

Examples of potential management options include:

- Options preventing or reducing infestations in the growing crop (e.g. pest management practices, monitoring, Integrated Pest and DIsease Management, etc.);

- Options ensuring that the area, place, or site of production is free from the pest (e.g. surveillance and monitoring, treatments, Pest Free Areas, Areas of Low Pest Prevalence);

- Options for application to consignments and commodities (e.g. post-harvest treatments, phosphine fumigation, inspections, etc.);

- Options for other types of pathways (e.g. certification of packing materials etc.);

- Options to be applied within the importing country (e.g. inspection, fumigation, heat or cold treatments, etc.);

- Prohibition or restriction of commodities;

- Requirement for phytosanitary certificate or other compliance measures;

- Systems approach.

For individual ISPMs relating to these management options, see the IPPC’s list of adopted Standards (ISPMs).

Conclusion

The pest risk management process results in either:

- No appropriate measures being identified,

- Or selection of one or more management options that have been found to lower the risk associated with the quarantine pest(s) to and acceptable level of protection (ALOP).

For a complete manual on how to develop PRAs, and list of resources (websites and references) see “Pest risk analysis (PRA) Participant manual from the IPPC“.

Image source: Plant Pest Risk Analysis, Concepts and Applications, by Christina Devorshak, CABI

Use of matrices in PRAs

- It might help to use a risk estimation matrix to assess the overall risk.

- A risk estimation matrix combines the likelihood of a pest entering, establishing and spreading with the potential consequences should that occur, and to determine whether specific risk management measures are required to achieve the ALOP.

- Matrices do not have to be symmetrical and this usually reflects a country’s ALOP.

Clarity, Transparency, and Consistency

Clarity and transparency

In methodology, and by listing assumptions and uncertainty.

Consistency

In criteria used for the analysis used to arrive to a conclusion.

What makes a good PRA?

A good PRA will recognise the sources of uncertainty and clearly describe what level of judgement has been applied and will recommend clear and unambiguous options.

It will be fully referenced.

Examples of Regional and Group PRAs

SALB APPPC

Regional PRA (click here)

-

A good example of a regional approach to developing a regional PRA (RSPM) for a high-risk pest of rubber, the South American Leaf Blight (SALB). This is an example of a Qualitative approach.

Mealybugs

Group PRA (click here)

- Group PRAs assess groups of pests with shared common biological characteristics. It improves the effectiveness and consistency in managing the risks associated with imported goods.

Australian examples of PRAs and IRAs

Import requirements for longans

From Viet Nam (2019) click here

11 Quarantine pests (guava, melon, and oriental fruit flies, several species of mealybugs, litchi fruit borer), and 2 thrips species were identified and required risk management measures.

Proposed risk management measures:

- Fruit provenance from pest free areas or fruit treatment (cold disinfestation or irradiation) for fruit flies, pre-export visual inspection for thrips, and mealybugs

- and the same risk management measures are listed for the litchi fruit borer.

Australian examples of PRAs and IRAs

PRA for cut flowers and foliage imports

Part I (2019) click here

Of all commodity types arriving in Australia, it was found that a high proportion of arthropod interceptions (23%) occurred on imported cut flowers and foliage and that imports had increased significantly in recent years. The PRA is done in two phases, with a first part dedicated to the predominant pests, including the three major arthropod pest taxa (mites, aphids and thrips).

The second part of this cut flowers and foliage PRA will be focussing on the remaining pests associated with these commodities, including the brown marmorated stink bug, exotic bees, the tarnished plant bug, some flies from the Agromyzidae family, as well as leafhoppers and sharpshooters with the potential to transmit Australia’s number one national priority plant pest, the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa.

Risk management options included (i) an NPPO-approved systems approach (ii) pre-shipment methyl bromide fumigation or alternative such as low temperature phosphine fumigation (iii) an NPPO-approved alternative pre-shipment disinfestation treatment (iv) on-arrival visual inspection.

Summary:

The great majority of countries develop PRAs/IRAs

Often using a qualitative approach

There is a push toward quantitative approaches but they are time consuming, expensive and complex.

Most countries will follow a qualitative approach and use matrices.

Judgement

Often there is a lack of scientific evidence and/or certain level of uncertainty for specific elements that will impact on the overall assessment of the risk.

It is essential to distinguish between decisions based on science, and those that are influenced by uncertainty.

PRAs have to be fully transparent, clear and consistent.

New tools are being developed to assist with the PRA process such as the Computer Assisted Pest Risk Analysis decision support-scheme (CAPRA) developed by the EPPO (European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation).

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)