for the Implementation of International Standards

related to Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)

Disclaimer

This e-learning module has been developed for the teaching purposes and material contained in it is of general nature.

It is not intended to be relied upon as legal advice and the concepts and comments may not be applicable in all circumtances.

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)

IPPC

This section is dedicated to the IPPC:

- how it came to be,

- what it does,

- and how it works.

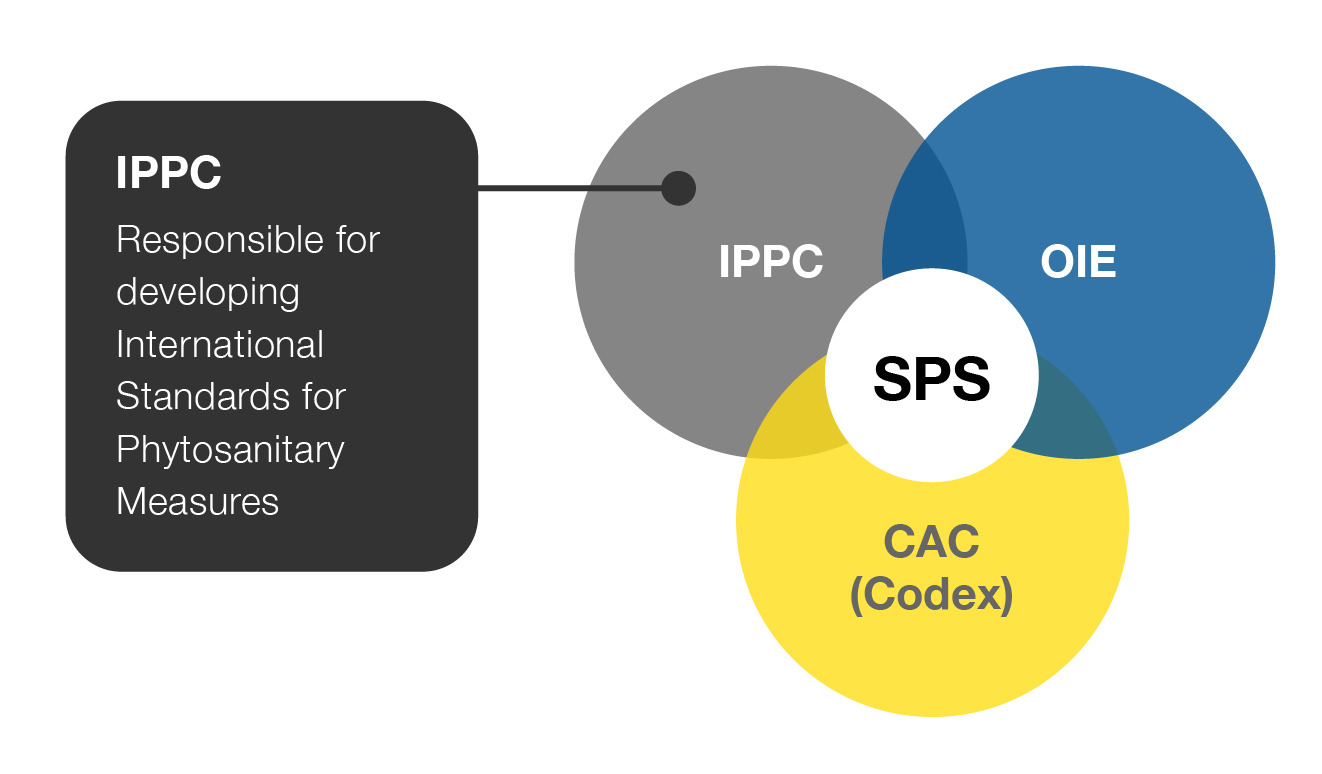

The 3 “sisters”

The 3 standard setting organisations recognised by the SPS Agreement are the IPPC, the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE)

IPPC and International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs)

We will be focusing on:

- Principles, rights, and obligations: Principles, Rights, and Obligations of contracting parties, and Governance

- ISPMs: Standards setting process, Categorisation.

The objective is

To give a broad overview of the IPPC’s governance and mission

France-Rouen (1660)

The necessity to protect plant health can be linked way back to the very first national agreement in Rouen, France in 1660. This agreement was dedicated to eradication of an alternate host of the stripe rust or black stem rust (BSR), Puccinia graminis Pers. responsible for stem rust on wheat and barley.

A law was passed in France making the eradication of barberry bushes in wheat growing areas mandatory and banning the planting of barberry near wheat fields.

At the time, little was known about important role barberry bushes were playing in the life cycle of the rust. It wasn’t until 1865, that a famous plant pathologist (Heinrich) Anton de Bary discovered the role of alternate hosts in the life cycle of this rust.

Image source: Emmanuel Byamukama, South Dakota State University, Bugwood.org

United States of America (1918)

Barberry bushes were introduced in the US in the mid 1700 and used as paddocks’ hedges.

In the US, a law to eradicate barberry bushes was enacted in Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut between 1726 and 1772.

To this day barberry eradication programs are still active in the US.

The control of alternate hosts in wheat production systems is becoming again an important issue particularly since Ug99 has emerged as the next biggest threat to wheat production systems and food security. (Ug 99 is a virulent rust that emerged in Uganda in 1999.)

Image source: Peterson, 2018

Irish Famine (1840-1847)

During the 19th century, several introductions of new pests and diseases had disastrous consequences in Europe starting with the famous potato famine caused the Oomycete pathogen Phytophthora infestans.

P. infestans was introduced from the Americas in the early 1840s, and devastated potato fields in Ireland where a big fraction of the population relied on this staple crop for survival.

Crop failures occurred several years in a row and led to what people call the Great Famine. The famine itself claimed around 1 million lives in Ireland.

To this day, P.infestans is considered one of the most costly potato pathogens to manage worldwide with an estimated $6 billion dedicated to its control in 2008. More recent suggest the total cost in Europe to be around 900 M€ per year.

Image source: Gillespie, Rowan: Famine (1997), commemorating the Great Famine, sculpture by Rowan Gillespie; in Dublin.

For more information of the great Irish famine see APSnet

Phylloxera vastratix (1860)

The second case story is the grape vine phylloxera known for a long time as Phylloxera vastatrix, or – an aphid native to North America (probably native to the eastern US).

In America, Vitis species native to North America that have co-evolved with Phylloxera, and the aphid induces galls on leaves and feeds on roots without any evident signs of injury.

In 1860 however, the aphid was introduced to France on American vines, which had been imported for use in breeding programs. The first report of Phylloxera was in 1963 in Languedoc Roussillon in the south west of France.

By 1863 some of the centuries-old vineyards in the Rhone valley had started to decline and within 10 years most had been destroyed. Phylloxera spread through France and destroyed an estimated 600,000 ha or about 2/3d of French vineyards. It then continued to spread through Europe. The economic and social effects in some areas of France were catastrophic, and many small viticulturists and wine makers migrated to South America and Algeria.

Europe was so concerned about the impact of this aphid that 5 European countries (Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Portugal and Switzerland) developed the first International agreement in 1878 to prevent the spread of a plant pest across borders: “The 1878 International Convention on measures to be taken against Phylloxera vastatrix”, signed in Bern (Switzerland) in 1881.

Image Source: 1882 map of rowing areas in France.

Coffee leaf rust (1869)

Coffee leaf rust was first reported in 1861 by a British explorer on uncultivated coffee in the Lake Victoria region of Kenya in East Africa. In cultivated coffee, it was first reported in Sri Lanka in 1869, and completely devastated coffee production in that country within 10 years. By the 1920s it was widespread in Africa and many of the Asian countries where coffee was grown commercially. It was reported and eradicated from Papua New Guinea three different times, until confirmed to be widespread there in 1965.

Berne treaty (1881)

Many of the principles now governing the IPPC were already present in the 1878 International agreement against Phylloxera vastatrix. In particular:

- The responsibility to give an official written assurance on Phylloxera-free provenance of host material being traded internationally;

- The prohibition of international trade in certain kinds of material that might spread the pest;

- The designation of official bureaux responsible for administering such trade;

- Powers to inspect traded material and take remedial action on items not complying with the requirements of the Convention;

- The prompt exchange of relevant information, particularly on new outbreaks; and finally-

- That all these measures were to be reflected in national law by the participant countries.

Following the 1881 convention, an additional convention was signed in 1889 in Berne.

To read the text, click here.

Image source: Central Science Laboratory, Harpenden , British Crown, Bugwood.org

International Agricultural Congress (1903)

Following the state of disarray of the agricultural sector in Europe in the 19th century, several congresses were dedicated to improving agriculture.

Before the first world war, at the International Congress of Agriculture and Forestry held in Vienna in 1890, a proposal was made to form an International Phytopathological Committee with the aim of controlling the spread of pests and diseases via trade. This committee was officially established at the International Agricultural Congress in Rome in 1903.

Image Source: University of Birmingham

The FAO (1946)

In 1900s, another very important conference took place in Rome, that eventually led to the establishment of the “International Institute of Agriculture” (or IIA for short), that is now the FAO.

It is at the IIA in Rome that the IPPC was formed after several conferences between 1914 and 1929 and the support of 40 countries.

In 1946 by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) succeeded the IIA.

Source: FAO home page

The IPPC (1952)

The second World War broke and the text of the Convention for the Protection of Plants was only ratified by 12 of the 46 signatory countries.

After the Second World War, the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) was adopted in 1952.

Image source: FAO

The IPPC Secretariat (1992)

In 1992 the IPPC Secretariat was established at FAO’s headquarters in Rome. In 1993, the international standard-setting program responsible for the development of ISPMs officially started.

Image source: FAO

Revisions of the IPPC text (1995)

The IPPC was revised in 1995 to take into account it’s role in relation to the WTO SPS Agreement.

Source: The history of the IPPC.

Adoption of revised text (2005)

The new revised IPPC text came into force in 2005.

To learn more about the History of the IPPC click here.

The actual text can be found here.

The IPPC mission

The IPPC vision is the protect global plant resources from pests;

The IPPC mission is to secure cooperation among nations in protecting global plant resources from the spread and introduction of pest of plants, in order to preserve food security, biodiversity and facilitate trade.

Image source: IPPC home page

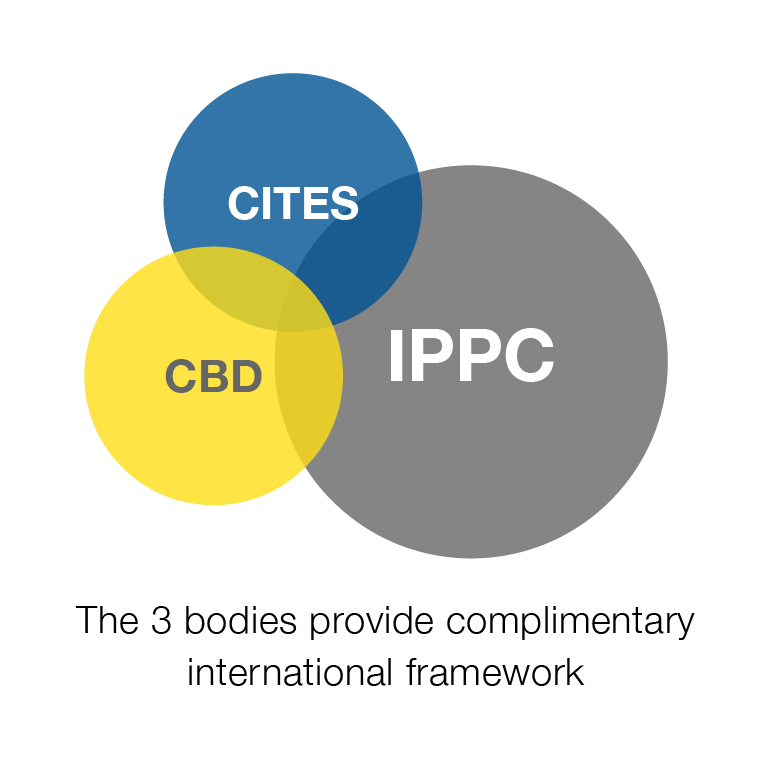

Links with other conventions

These are other conventions concerned with the protection of plants.

IPCC

The IPPC vision is to protect global plant resources from pests

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

The CBD aims to conserve biological diversity and, in the specific case of invasive alien species, to protect ecosystems, habitats or species

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

CITES is concerned with endangered species and its aim is to ensure that international trade of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival.

Introduction

Being a signatory to the IPPC binds countries with both rights and obligations.

Obligations under the IPPC are consistent with and complementary to those of the SPS Agreement.

There are currently 183 (September 2019) contracting parties to the IPPC.

You can find the list of contracting parties to the IPPC here.

Rights

Countries signing the IPPC become “contracting parties or signatories”.

By signing the Convention, the countries express their intention to comply with the IPPC.

By signing the Convention, signatories:

- Have sovereign authority to use phytosanitary measures to regulate the entry of plants and plant products and other objects or material capable of harbouring plant pests.

- Can refuse entry, require treatment or specify other requirements for regulated material.

- Have the right to take emergency action on the detection of a pest posing a potential threat to their territories.

Image source: Brown Marmorated Sting Bug

Obligations

In applying phytosanitary measures, contracting parties have obligations to comply with the Convention’s 11 core principles of:

- Sovereignty,

- Necessity,

- Managed risk,

- Minimal impact,

- Transparency,

- Harmonisation,

- Non-discrimination,

- Technical justification,

- Cooperation,

- Equivalence of phytosanitary measures,

- Modification.

You will find the 28 principles listed and explained in ISPM 1. If you have never read ISPM 1 please take a few minutes to do it now.

These principles are similarly reflected in the SPS Agreement. In brief, phytosanitary requirements must be scientifically justified, consistent with the pest risk analysis and result in the minimum impediment to international trade.

Designing an NPPO

Another obligation of signatories is the nomination of a contact point or a National Plant Protection Organisation (NPPO) who is usually the official services of government bodies (e.g. a representative from the Department of Agriculture).

The responsibilities of the NPPOs are:

- Issuance of phytosanitary certificates,

- Surveillance and inspection,

- Notifying trading partners of non-compliance with import requirements and emergency actions taken,

- Exchanging information on pests of plants (including pest reporting),

- Base their phytosanitary measures on risk assessment and analysis (conducting pest risk analyses or PRAs).

For more information on NPPOs click here.

Regional Plant Protection Organizations

The Convention also encourages contracting parties to cooperate on a regional basis and form Regional Plant Protection Organisations (RPPOs).

RPPOs usually perform a coordinating function to gather and disseminate information, and address technical issues of a regional nature.

There are now (September 2019) 10 RPPOs:

APPPC: Asia and Pacific Plant Protection Commission

CFHSA: Caribbean Agricultural Health and Food Safety Agency (CAHFSA)

CAN: Comuunidad Andina de Naciones or Andean Community

COSAVE: Comite de Saniadd veetal del Cono Sur or Southern Cone Plant Health Committee

EPPO/OEPP: European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization/Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes

IAPSC: Inter-African Phytosanitary Council NAPPO: North American Plant Protection Organization

OIRSA: Regional International Organisation for Agricultural Health PPPO: Pacific Plant Protection Organization

NEPPO: Near East Plant Protection Organization

RPPOs have their own regional programs and they may assist the IPPC in converting IPPC documents into local languages;

RPPOs may consider and propose new international standards or provide additional information from a regional perspective;

RPPOs may develop their own standards (RSPMs) to use within their region. Some predate the current ISPMs.

Note that governments can belong to RPPOs without being contracting parties to the IPPC, and a government can belong to more than RPPO.

The role of the IPPC Secretariat is to support the IPPC governing bodies and coordinate the IPPC work programs.

The IPPC Secretariat is based at the FAO headquarters in Rome.

For more information on the secretariat’s role, click here

In 1993, the Committee of Experts on Phytosanitary Measures (CEPM) was established with the objective of developing ISPMs. The CEPM became later the Commission on Phytosanitary Measures (CPM).

The CPM is the governing body of the IPPC.

What does the CPM do?

- CPM reviews the state of plant protection around the world;

- CPM identifies actions to control the spread of pests into new areas;

- CPM develops and adopts international standards;

- CPM establishes rules and procedures for resolving disputes;

- CPM establishes rules and procedures for the sharing of phytosanitary information; and

- CPM cooperates with international organisations on matters covered by the Convention.

The CPM meets every year in March or April. For more information on the CMP, click here.

Image Source: IPPC

Since the establishment of its standard setting function in 1993, 43 ISPMs have been developed by the IPPC (one is revoked).

Contracting parties are invited to provide topics for the development of new ISPMs through a call for topics.

A first draft ISPM is developed by an expert working group (EWG) and submitted to the Standards Committee (SC). The Standards Committee reviews and modifies the draft as necessary and then it is submitted to NPPOs and RPPOs for consultation.

It can take several years for an ISPM to be drafted and several rounds of expert consultation to reach completion.

To learn more about the standards setting process, click here.

In 2006, the CPM established the Standards Committee (SC). The SC consists of 25 members from the 7 FAO regions. The Standards Committee’s roles are to:

- Oversee the IPPC’s Standard Setting Process

- Manage the development of International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs);

- Oversee and provide guidance to Expert Working Groups (EWGs) and Technical Panels (TPs).

The CPM has another subsidiary body called the Subsidiary Body on Dispute Settlement where signatories can call on experts to assist with interpretation and applications of the IPPC.

Source: IPPC May 2018

As discussed previously, RPPOs can develop RSPMs that reflect the need to control a pest in their region or because they are using different protocols to the ones already existing.

As discussed previously, RPPOs can develop RSPMs that reflect the need to control a pest in their region or because they are using different protocols to the ones already existing.

We have given examples of RSPMs that were eventually adopted as ISPMs.

NAPPO RSPM 32 on Pest Risk Assessment for Plants for Planting as Quarantine Pests (Archived below) is now superceded by ISPM 11

APPPC’s RSPM 7 on Guidelines for the protection against South American leaf blight of rubber.

Additionally, both the IPPC Secretariat itself or/and the WTO-SPS Committee can propose ISPMs topics.

Image source: IPPC An introduction to the IPPC standard setting process

The IPPC Secretariat makes a call for ISPMs topics every two years.

Contracting parties and RPPOs submit detailed proposals for new topics or for the revision of existing ISPMs to the IPPC Secretariat.

They are asked to send a range of justification documents and reviews with their submission. The application is reviewed by the SC and added to the list of topics for ISPMs.

Image Source: IPPC /Core activities/Standards & implementation/Standard setting

So far, there are 43 ISPMs (September 2019).

Where to find them?

IPPC web site: https://www.ippc.int Home/ Core Activities / Standards & Implementation / Standard setting / Adopted Standards (ISPMs) And select the IPSM you want to download and the language you want it in.

The first entry of the table is the complete list of ISPMs.

Click here to go to the IPPC’s ISPMs list.

Most ISPMs are interlinked and recent material has been added to cover diagnostic protocols (DPs) and phytosanitary treatments (PTs).

Some ISPMs are broad and underpinning whereas some are more specific. ISPMs can be categorised into:

- Core or reference standards;

- Concept standards;

- Specific standards; or

- Pest Risk Analysis standards.

Reference standards provide general guidance for the development and operation of plant health procedures, including the use of specific terms and terminology.

Core reference standards are:

ISPM 1: “Phytosanitary principles for the protection of plants and the application of phytosanitary measures in international trade” (adopted in 1993, revised in 2006). ISPM 1 assist with the development of other ISPMs by providing the link to the SPS Agreement through the list of Principles governing the IPPC.

ISPM 5: ”Glossary of phytosanitary terms” (updated as needed) Supplement 1: Guidelines on the interpretation and application of the concept of “official control” and “not widely distributed” (2012) – Supplement 2: Guidelines on the understanding of “potential economic importance” and related terms including reference to environmental considerations (2003) –

Appendix 1: Terminology of the Convention on Biological Diversity in relation to the Glossary of phytosanitary terms (2009)

Image source: IPPC

The definition of a pest is: ”Any species, strain or biotype of plant, animal or pathogenic agent injurious to plants or plant products. Note: In the IPPC, “plant pest” is sometimes used for the term “pest” [FAO, 1990; revised ISPM 2, 1995; IPPC, 1997; CPM, 2012].

The definition of a pest is: ”Any species, strain or biotype of plant, animal or pathogenic agent injurious to plants or plant products. Note: In the IPPC, “plant pest” is sometimes used for the term “pest” [FAO, 1990; revised ISPM 2, 1995; IPPC, 1997; CPM, 2012].

The IPPC recognises different categories of pests:

- A quarantine pest (QP): “A pest of potential economic importance to the area endangered thereby and not yet present there, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled” [FAO, 1990; revised FAO, 1995; IPPC 1997].

- A regulated non-quarantine pest (RNQP). “A non-quarantine pest whose presence in plants for planting affects the intended use of those plants with an economically unacceptable impact and which is therefore regulated within the territory of the importing contracting party” [IPPC, 1997].

- A regulated pest (RP): “A quarantine pest or a regulated non-quarantine pest” [IPPC, 1997]

- Contaminating pests (CPs): Previously known as hitchhiker pests. A contaminating pest is “A pest that is carried by a commodity and, in the case of plants and plant products,do es not infest those plants or plant products” [CEPM, 1996; revised CEPM, 1999]

The terms “ alien species or invasive pests” are used by other conventions (e.g. CBD) and “exotic, endemic, indigenous, high-risk etc.” whist valid, are not terms used by the Convention.

Image source: E. Richard Hoebeke, Cornell University, Bugwood.org

Another definition is ”Regulated articles”:

“Any plant, plant product, storage place, packaging, conveyance, container, soil and any other organism, object or material capable of harbouring or spreading pests, deemed to require phytosanitary measures, articularly where international transportation is involved” [FAO, 1990; revised FAO, 1995;IPPC, 1997].

Image source: IPPC

Concept standards describe the key activities that NPPOs need to undertake to protect themselves from the impact of pests and include activities such as surveillance, establishment of pest status, phytosanitary certification, pest free areas, eradication programs and set up of post-entry quarantine facilities.

Concept standards describe the key activities that NPPOs need to undertake to protect themselves from the impact of pests and include activities such as surveillance, establishment of pest status, phytosanitary certification, pest free areas, eradication programs and set up of post-entry quarantine facilities.

Examples of topics covered by concepts standards are:

- Surveillance: ISPM 6

- Certification systems & Phytosanitary certificates & inspection & sampling : ISPM 7 & 12 & 23 & 31

- Pest free areas, places of production and production sites and areas of low pests prevalence: ISPMs 8 & 10, 22, 29 (ISPM 30 is revoked)

- Eradication programs: ISPM 9

- Non-compliance and emergency action: ISPM 13

- Regulated non-quarantine pests: ISPM 16

- Pest reporting: ISPM 17

- Lists of regulated pests: ISPM 19

- Phytosanitary import regulatory systems & compliance: ISPM 20

- Equivalence of phytosanitary measures: ISPM 24

- Consignments in transit: ISPM 25

- Categorisation of commodities according to their risk: ISPM 32

To find links to the individual ISPM, check the table of adopted standards on the IPPC website.

Image source: IPPC

Specific standards are developed for given pests, commodities, packaging or conveyances.

Specific standards are developed for given pests, commodities, packaging or conveyances.

One example is ISPM 15 on “Regulation of wood packaging material in international trade (adopted in 2002, revised in 2009, Annex 1 and 2 revised in 2013 and in 2018).

“Guidelines for the use of irradiation as a phytosanitary measure” (ISPM 18), is another example of specific ISPM for phytosanitary treatments.

Then a whole range of ISPMs are focusing on specific pests, such as fruit flies (ISPM 26 on PFAs, ISPM 35 & 37), some of which are diagnostic protocols (ISPM 27 DPs 1 to 29) for a whole range of invertebrates pests, some fungi, viruses, viroids, nematodes, bacteria of phytosanitary significance.

ISMP 28 provides guidance on Phytosanitary treatments for regulated pests (PT 1 to 32) and protocols for cold treatments, fumigation, vapour heat treatments and irradiation.

There are also a range of more recent ISPMs dedicated to propagating and planting material, and their movement in international trade (ISPM 33, 36, 38, 40).

To find links to the individual ISPM, check the table of adopted standards on the IPPC website.

Image source: IPPC

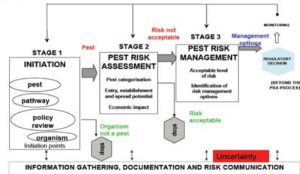

ISPMs specifically developed for pest risk analysis are:

ISPM 2: “Framework for pest risk analysis” (adopted in 1995, revised in 2007)

ISPM 11: “Pest risk analysis for quarantine pests” (adopted in 2001, revised in 2004 & 2013)

ISPM 21: “Pest risk analysis for regulated non-quarantine pests” (adopted in 2004)

And of course the whole suite of ISPMs as individual or combined measures to appropriately address the risk.

To find links to the individual ISPM, check adopted standards on the IPPC website.

Image source: IPPC

Even though contracting parties have rights and obligations, ISPMs are not legally biding.

In other words, it is not compulsory to use them – however contracting parties are encouraged to use them and when doing so, to consider them in their entirety (as a whole).

For additional material click here.

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)