for the Implementation of International Standards

related to Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) Measures

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)

Disclaimer

This e-learning module has been developed for the teaching purposes and material contained in it is of general nature.

It is not intended to be relied upon as legal advice and the concepts and comments may not be applicable in all circumtances.

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)

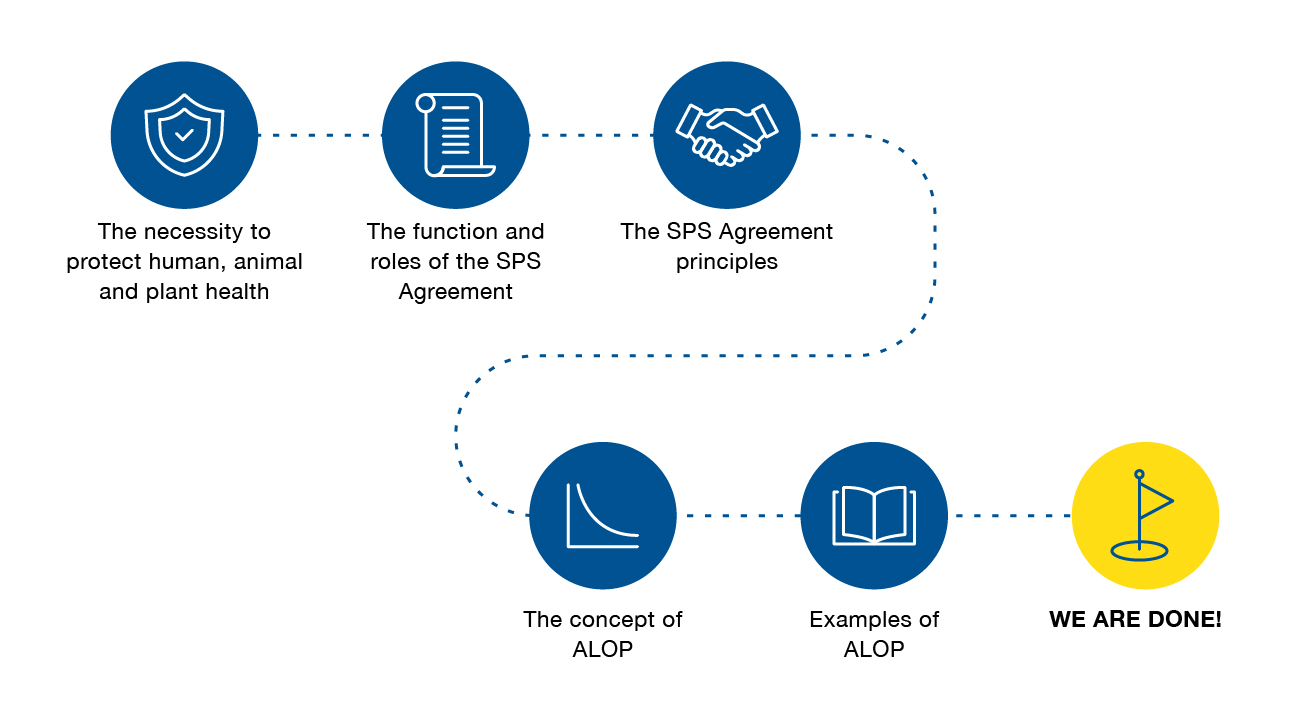

Recall from 1.1

- Increasing trade activity results in increasing risk to countries.

- The Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (The SPS Agreement) is concerned with food safety, animal, and plant health regulations.

This section is dedicated to the SPS Agreement

- what it is,

- what it does,

- how it came to be.

The objective is

To give you a board overview of the SPS Agreement and its relationship with the 3 International standard setting bodies, the IPPC, the OIE, and Codex

A bit of history…

How did the SPS Agreement begin?

Introduction

The SPS Agreement was adopted by Members on January 1st 1995, the same time as the establishment of the WTO.

The full text of the SPS Agreement appears in the Act resulting from the Uruguay round of multilateral trade negotiations.

However, negotiations for the SPS Agreement began well before 1995.

In fact – what came to be the SPS Agreement as we know it today, started with the GATT in 1948.

Image source: WTO Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures

GATT Articles I and XXb

Article I of the GATT, called “the most favoured nation clause”, required non-discriminatory treatment of imported products from the different foreign suppliers.

This article established the principle of non-discrimination which is one of the core principles of the SPS Agreement today.

Further, Article XXb (20b) of the GATT is the very basis of the SPS Agreement. Article XX(b) stated that countries have the right to apply SPS measures to protect human, animal, or plant life or health.

GATT’s Article XXb declared that these measures to protect human, animal, or plant life or health should not result in disguised restrictions to trade. In other words, whatever is put in place by an importing country to protect oneself from the impact of pests and diseases resulting from trade should not result in arbitrary and unfair trade barriers.

For some information see FAQ’s History of the SPS Agreement

Harmonisation (Tokyo)

During the Tokyo round of GATT negotiations between 1973 and 1979, another Agreement called the Agreement on Technical barriers to Trade (or the 1979 TBT Agreement) was established.

Signatories to the 1979 TBT Agreement also agreed to use relevant international standards such as those for food safety developed by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, or the ISPMs developed by the IPPC.

This Agreement to adopt international standards is the beginning of the current principle of harmonisation of the SPS Agreement.

For some more information see WTO TBT Agreement and technical barriers to trade.

Transparency (Tokyo)

Another important outcome of the Tokyo round was the discussions around notification to Governments of any technical regulations which were not based on agreed international standards.

This was the basis for the development of another essential principle of the current SPS Agreement, the principle of Transparency.

One of the many objectives of the Uruguay round, was to reduce barriers to agricultural trade.

3 areas in the agricultural sector were discussed during the Uruguay round, namely:

- market access;

- direct and indirect subsidies; and

- sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures.

Harmonisation (Uruguay)

The additional important topic discussed during the Uruguay round was the elimination of all restrictions or measures that lack any valid scientific basis.

This is another essential principle of the SPS Agreement: any measure implemented to protect human, animal, and plant life and health from the adverse impact of trade needs to be based on sound scientific evidence.

For more information see The WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement)

Sovereignty

The SPS Agreement confers the right to WTO Member countries to apply measures necessary to protect human, animal, and plant life and health.

The SPS Agreement sets out the basic rules and requirements for many other conditions such as import licenses, inspection requirements, testing and certification requirements, labelling, packaging requirements, quarantines, etc.

The SPS Agreement is essentially about protecting health in an active global trading system.

The SPS Agreement recognises the need for WTO Members to protect themselves from the risks posed by the entry of new pests and diseases through Trade, Transportation, Tourism, and Travel – what we call the 4 “Ts” which leads us to another core SPS principle which is the principle of Sovereignty.

But remember that the SPS Agreement is also about minimising any negative impacts of SPS measures on international trade.

The three sisters

The SPS Agreement is about setting up parameters, and rights and obligations of Member countries; and the most important right is to be able to protect one’s country against the potential deleterious impacts of trade on food safety, animal, plant, and health. The SPS Agreement says you can do this but doesn’t tell you how.

For example, the SPS Agreement does not give guidance on fumigating a consignment at arrival, what diagnostic test you should use to detect foot and mouth disease or how to detect aflatoxins in peanut butter;

Instead, the SPS Agreement give the necessary power to 3 international standard setting bodies to develop a range of standards, recommendations, and guidelines to assist trading countries with the appropriate took to reduce the risk posed by trading activities, travel, transportation and tourism (our 4 Ts).

The SPS Agreement recognises three such international standard setting bodies:

- The Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) also called Codex for food safety, jointly administrated by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the World Health Organisation (WHO);

- The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE); and

- The International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) for plant life and health administrated by FAO

These 3 bodies are referred to as the “3 sisters”.

For more information on the 3 standard setting bodies recognised under the WTO SPS Agreement, click here

Regionalisation

Another principle of the SPS Agreement is the principle of regionalisation. Regionalisation recognises that SPS measures should be adapted to the SPS conditions found in the country of origin.

This is to reflect the fact that the same commodity produced in two different countries might host a completely different range of pests and diseases and represent different risks to an importing country.

The SPS measures imposed should reflect the difference in risk for the same commodity produced in different countries.

ALOP

WTO Members are entitled to maintain a level of protection they consider appropriate to protect human, animal, and plant health. This is what we call the ALOP.

Another way to describe the ALOP is as an acceptable level of risk or a tolerable level of risk.

By defining an ALOP, Member countries set a base-line for what they see as an acceptable risk and will negotiate and implement appropriate SPS measures to lower the risk associated with imports to meet their ALOP.

For some information of the ALOP, see GASCOINE, D. “The ‘Appropriate Level of Protection’: an Australian Perspective.” The Economics of Quarantine and the SPS Agreement, edited by Kym Anderson et al., University of Adelaide Press, South Australia, 2001, pp. 132-140. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851/j.ctt1t304rx.13.

Equivalence

An ALOP can be met many ways, meaning that different SPS measures can lead to the same result, which is ultimately to meet the country’s ALOP. In that case, these measures are equivalent in their outcomes.

Under the principle of equivalence, the SPS Agreement states that Governments should accept different measures which provide the same level of health protection for food, animals, and plants.

In other words – if a domestic measure is different from international measures but provides the same level of protection, then it should be accepted as an appropriate and valid measure to meet the importing country’s ALOP.

Typically, recognition of equivalence is achieved through bilateral consultations and the sharing of technical information.

For some more information see the IPPC document on Equivalence, a review of the equivalence between phytosanitary measures used to manage pest risk in trade

Summary

As the WTO Uruguay round of negotiations progressed, it was agreed in 1988 that:

- SPS measures should not represent disguised trade barriers;

- SPS measures should be harmonised on the basis of generally-accepted (or sound) scientific evidence;

- Special consideration should be given to emerging economies

- Transparency should be ensured in setting regulations but also in solving disputes; and

- An international committee should be established to provide for consultations regarding standards.

Eventually, the final text of the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measure (the SPS Agreement) was approved at the end of the Uruguay round and entered into force on the 1st January 1995.

Rights and Obligations

We have seen most of the 14 SPS Agreement articles containing the rights and obligations of the WTO Members.

- The principle of non-discrimination,

- The principle of necessity,

- The principle of harmonisation,

- The principle of transparency,

- The principle of sovereignty,

- The principle of equivalence,

- The principle of regionalisation.

The appropriate level of protection

Establishing an ALOP or “level of acceptable risk”

Under the SPS Agreement, Members are entitled to maintain a level of protection they consider appropriate to protect human, animal, and plant health.

A country’s ALOP is then reflected in local legislation, policies, and measures.

Another way to describe the ALOP is as an “acceptable level of risk” or “a tolerable risk”.

Introduction

Risk is a function the consequence of an event and the probability of its occurrence. Image source: ITC

Basically it is the product of a probability by a consequence. We can reflect risk in a two-dimensional (probability/consequences) space as seen on this graph.

Commodity B

Commodity B is bearing a risk that is much greater than the ALOP and the risk associated with this commodity is unacceptable and needs to be lowered by using SPS measures to meet the importing country’s ALOP. If the risks associated with commodity B cannot be reduced to the ALOP, then the goods should not be imported until suitable measures are identified and agreed on. Every situation will be different and the risk per commodity type and country of origin will vary. The risk will also vary with the number and diversity of pests and diseases found on the commodity and the propensity or ability of the associated pests and diseases to enter, establish, spread and cause damage which is inherently linked to their biology.

Summary

The ALOP is a difficult concept to understand, I hope this helped. For more information on ALOP, see chapter 7 “appropriate level of protection: an Australian perspective”, written by Digby Gascoine, in “The Economics of Quarantine and the SPS Agreement” by Kym Anderson, Cheryl McRae and David Wilson.

ALOP concept summary

- No country can express its ALOP in precise terms across sectors.

- An unrealistic ALOP that doesn’t reflect the SPS status of a country can lead to unfair trade practices.

WTO Member countries have the right to implement SPS measures, as long as they do not unfairly restrict trade. When considering their ALOP, countries must consider their own SPS status.

There are many factors to take into consideration and these are outlined in the following slides.

If a country is a net imported of agriculture goods because their domestic sector is small and only represents a very small fraction of their GDP, they have less to lose from the importation of pests and diseases.

On the other hand, for net exporters of agricultural products, new pests and diseases can have very severe consequences.

If agriculture practices are relatively recent and a country benefits from biological isolation (e.g an island, an ice-covered country or a country surrounded by desert) this country could consider their general SPS status to be very high because there has not been time or the physical conditions (e.g land borders) for the introduction of transboundary pests and diseases.

On the other hand, if a country is in a middle of a big continent with many shared borders, and has been involved in trade and agricultural practises for a very long time it is likely to have more transboundary pests and diseases and hence a lower SPS status.

Introduction of new pests and diseases into a country that is heavily reliant on subsistence farming could have impacts that are unaffordable to manage.

Some countries many have a significant environmental asset-base in the form of large wild and protected areas (national parks, native forests, etc.) or be a centre of origin for a range of species. These countries’ may wish to protect the environmental resources.

Assessing the potential environmental impact is notoriously difficult often because it is difficult allocate an economic value to environmental assets and also because there is less information available compared to agricultural systems.

It is difficult to predict the biological and ecological impact of an introduced organism in a new environment.

A wealthy country with a high standard of living is more likely to benefit from international trade in agricultural products and is most likely to invest in a complex and effective SPS systems to protect itself.

Wealthier countries are more likely to establish effective early surveillance systems, and are better equipped to deal with the high-cost of incursion management and potential on-going control strategies if eradication fails.

Considering these factors, how should a country determine it’s ALOP?

Defining ALOP with precision and applying it on a consistent basis across sectors, is difficult to achieve and maintain.

For instance, Australia’s ALOP is expressed as ‘providing a high level of SPS protection aimed at reducing risk to a very low level, but not zero.”

How to define an ALOP?

Consider:

- level of biological isolation (including borders and history of agriculture)

- Net importer or exporter

- Industrialised or subsistence

- Environmental assets

- Capacity to respond

No country has given a clear and unequivocal definition of their ALOP.

Under the SPS Agreement, measures should be:

Where to find additional information?

- Text of the SPS Agreement click here

- Introduction to the SPS Agreement click here

- International Trade Centre (ITC) click here

Introduction

The SPS Agreement sets new rules in an area previously excluded from GATT’s disciplines in that it gives the right to Members to apply SPS measures that might restrict trade in order to protect themselves from pests and diseases.

There are other important concepts and key features in the SPS Agreement that haven’t been discussed. These are briefly listed here.

You will find them under the Annexe A (Definition) of the SPS Agreement.

PFA and ALPPs

Under the SPS Agreement, Members are committed to recognising the concepts of pest-free areas (PFAs) and areas of low pest prevalence (ALPPs) and should adapt their phytosanitary requirements to the conditions of the area from which a product originates.

The SPS Agreement in its Annex A defines :

a. A pest-free areas (PFA) as: An area (entire country, part of a country, or all or parts of several countries), as identified by the competent authority, in which a specific pest or disease does not occur.

b. An area of low pest prevalence (ALPP) as: An area (entire country, part of a country, or parts of several countries), as identified by the competent authority, in which a specific pest or disease occurs at low levels and which is subject to effective surveillance, control or eradication measures.

For more information click here.

Applying higher standards than international ones

By default, the SPS Agreement encourages Members to adhere to international standards from the “3 sisters” where they exist (i.e. ISPMs for the protection of plant health).

However, higher standards can be if they are required to address the risk-posed.

The condition here is that stricter measures, if deemed necessary, should be scientifically justified.

Risk assessment

The SPS Agreement clearly states in article 5 that “Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures are to be based on an assessment of the risks to human, animal and plant life and health using internationally accepted risk assessment techniques”.

Risk assessment should take into account:

- Available scientific evidence;

- Relevant processes and production methods;

- Inspection/sampling/testing methods;

- Prevalence of specific diseases or pests;

- Existence of pest/disease free areas;

- Ecological/environmental conditions;

- Quarantine or other treatment.

Risk assessment for animal and plant health should take into account economic factors such as:

- Cost of control or eradication;

- Potential damage or loss of production/sale;

- Cost effectiveness of alternative approaches.

ECONOMIC COOPERATION SUPPORT PROGRAMME (AECSP)